His principles were not kept in the pocket of a Sunday coat (I don’t know that he always had a Sunday change of any sort); but were to him the daily light which led his steps.

W. J. Linton, ‘Who were the Chartists?’, The Century, Apr. 1882.

Today the news is at our fingertips, we can access it any time, anywhere. With the advent of the internet and social media, television and radio, we have more ways than ever before to find out what is going on in the world around us. However, in Regency Britain, the period between 1811 and 1820 when King George III was deemed unfit to rule and his son ruled as Regent in his place, things were different. The main way that ordinary people could find out about events in the wider world was through newspapers. But under the Prince Regent, the government raised an existing tax on newspapers to 4d. a copy in 1819, a level which meant that working class people couldn’t afford the news. Workers could expect to earn a few pence a day for twelve hours of work, which meant that they were being priced out of the mass market for news and knowledge consumption. In response, Henry Hetherington, a London printer, defied the tax and published The Poor Man’s Guardian priced at one penny a copy. This lead to his prosecution and repeated imprisonment but eventually the campaign to repeal “taxes on knowledge” succeeded.

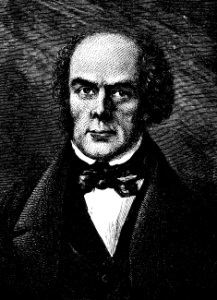

Henry Hetherington had trained as a printer with Luke Hansard and by 1822 was able to set up his own printing and book-selling business. Throughout the 1820s he was already involved in cooperative and radical movements. In particular, he supported the early London Cooperative bodies based on the ideas of Robert Owen, including the London Mechanics’ Institute (now Birkbeck College, University of London). From 1830 to 1835 he published newspapers priced at one penny, first the Penny Papers for the People (a daily published from 1830 – 31) then the Poor Man’s Guardian (a weekly published from July 1831 to December 1835). Hetherington made clear his intention to defy the tax, giving the paper a heading saying “Published contrary to ‘law’ to try the power of ‘might’ against ‘right’”.

In June 1831 Hethrington was summoned to Bow Street Magistrates Court where he was found guilty of selling an unstamped newspaper and fined £5. In court he stated his intention not to pay this fine, which lead to a second £5 fine, but he was released when friends offered surety for him. The Bow Street magistrates sent a further summons to Hetherington but he sent a response that he wouldn’t attend as he was going away. A warrant for his arrest was then issued. Hetherington was then sentenced to six months imprisonment at Clerkenwell New Prison, and all because he wanted to make the news accessible to ordinary workers.

Whilst Hethrington was in prison, the authorities tried to supress the circulation of the Poor Man’s Guardian by arresting and convicting vendors who were selling without a Hawker’s Licence. This was happening by the fourth edition of the newspaper and by the sixth issue The Poor Man’s Guardian was reporting the arrests of its vendors and funds were being collected to support them. The strategy being followed by Hetherington and his friends was to keep going and attract as much publicity as possible. Some of the vendors used arrest to make their own statements against the tax, which were also reported in the press more widely.

It is estimated that 724 men, women and children were arrested for selling The Poor Man’s Guardian. Some were repeat offenders, such as Edward Hancock who told Alderman Kelly when on trial at the Guildhall that “being unrepresented, I am not bound to obey any laws. Henry Hetherington and I are prepared to make a start by disputing the stamp law. To defy one is quite enough at a time we find.” [Reported in The Poor Man’s Guardian on 13th October 1832.]

It was not until 1836 that the tax on newspapers was reduced to 1d – its pre 1819 level.

After Henry Hethrington’s death in 1849, the Association for Promoting the Repeal of Taxes on Knowledge continued pressing for complete removal of tax from pamphlets, advertisements and newspapers, supported by a speech in Parliament by the future Liberal Prime Minister, William Gladstone. By the mid-1850s they succeeded.

By Barbara Lister

Barbara Lister is a U3A researcher for the Citizens project.